Watch trailer

These screenings will be in Japanese with English subtitles. Showtimes for dubbed screenings can be found here.

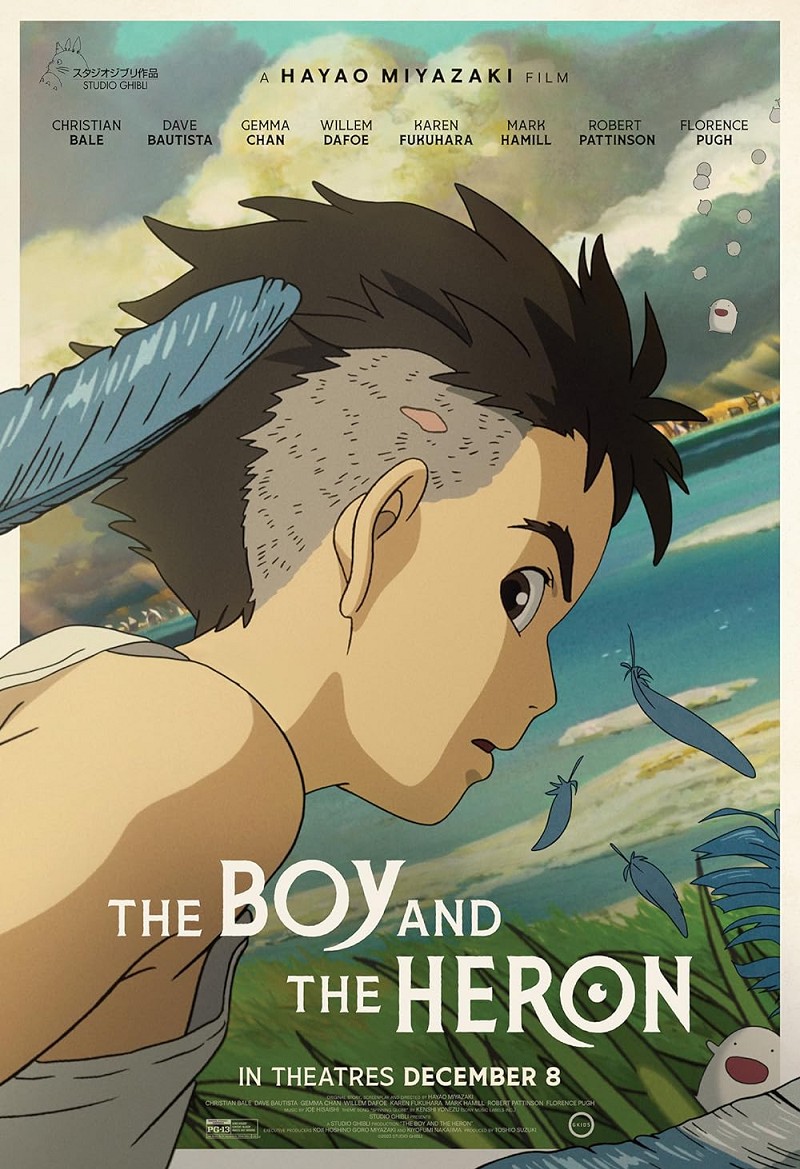

As World War II continues to rage, 12-year-old Mahito is relocated to his father and new stepmother's country estate. While he struggles to settle into his new life and grapple with his mother's tragic death, his strange new world suddenly becomes even stranger: he encounters a mysterious talking heron, who informs Mahito that his mother is still alive. Determined to find her, he ventures into an abandoned tower which whisks him away to a fantastical realm filled with creatures both strange and familiar.

The Garden Cinema View:

Whilst sources indicate that Hayao Miyazaki has been spotted around Studio Ghibli potentially failing to retire once again, his latest effort is imbued with a sense of career and personal reflection, and packed with references to his (and his collaborators’) prior work. The Boy and the Heron begins with parental loss that evokes both My Neighbour Totoro and the late Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies. In fact many of Miyazaki’s (young) protagonists are orphaned in actual or symbolic capacity, and most find themselves in periods of transition marked by relocation to unfamiliar surroundings. And like the rural locations of Spirited Away, Totoro, and When Marnie was There, Lewis Carrollian doorways into magical mirror worlds await.

The fantasy space of The Boy and the Heron is densely layered, and the Miyazaki’s paces the picaresque adventure at a brisk clip that recalls some of his 1980s anime such as Nausicaä and Castle in the Sky. Further direct references abound to Ghibli’s past, and ocean sequences allude to one of Miyazaki’s great influences: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series, of which the adaptation by Miyazaki’s son Goro must rank as a significant disappointment in a career of triumphs. At the centre of this film lies a Prospero figure, an aging wizard ready to lay down his staff. Surely this is Miyazaki? His own producer thinks that the young protagonist is a better fit for the director.

This is one of many questions with several possible answers in The Boy and the Heron, and the frame of self-reference can be hard to process on first viewing, even (perhaps especially) for Ghibli veterans. There is a sense of Miyazaki’s desire to pack every idea into his potentially final film. As such, The Boy and the Heron lacks to clarity of vision and profound sense of place of his finest works. There is, however, nothing like the films of Miyazaki, and any new work is an absolute gift to cinema.