The Garden Cinema presents, for the first time in the UK, an in-depth exploration of Japanese filmmaking from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. A span of time that brings together legendary directors and actors, and which produced a body of enduring masterpieces: Japanese cinema’s Golden Age.

This period of sustained artistic innovation emerged from unprecedented social upheaval and radical shifts in national ideology. Much like early Italian Neorealist works, films made in Japan in the years immediately following WWII bear the visible scars of the conflict in bomb-damaged location scenes, and productions suffered with scarce resources and funding. The effect of US censorship on Yasujiro’s Ozu’s masterpiece from this period, Late Spring (1949), reminds us that Japan was a country under occupation for seven years after the war. Centuries of feudalism were replaced by General MacArthur’s drive for democratisation, political freedom, and labour unionism. But facing McCarthyism at home, and rising cold war tensions in the region, this attempt of social democracy was itself reversed in favour of remilitarisation, pro-market capitalism, and, indeed, support for the now un-deified Emperor. A merry-go-round of competing ‘truths’ that aligns with the first Japanese film to truly impact the West, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950).

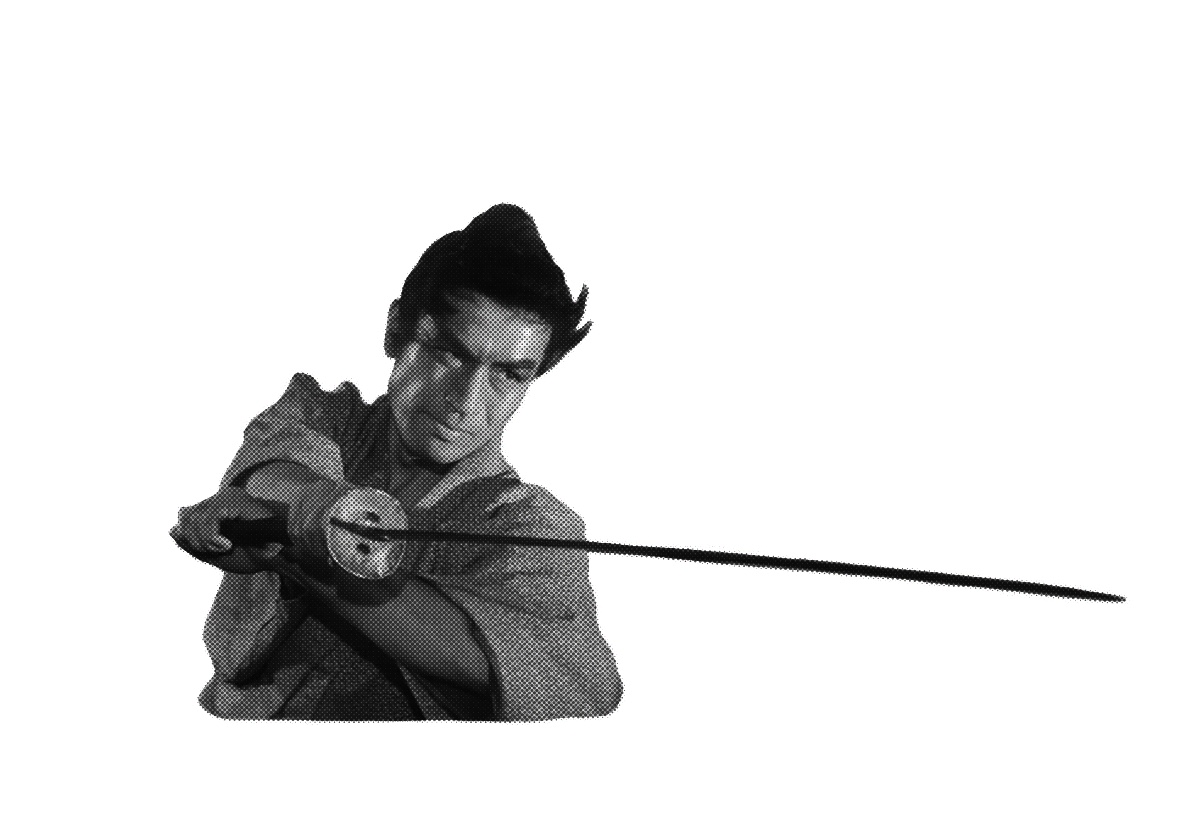

The loosening of business restrictions alongside vast injections of capital, led to the Japanese economic miracle, and rapid modernisation of industry and society. The tensions and possibilities produced by these shifts provided rich material for filmmakers in Japan. Two of Kurosawa’s great films from the early 1950s, Ikiru (1952), and Seven Samurai (1954), show the need, respectively, for individual acts of decency, and the power of collective action. The painterly jidaigeki (period dramas) of Kenji Mizoguchi, such as Sansho the Bailiff (1954), demonstrate an uneasy nostalgia for the honourable codes of the feudal past that conversely crush individuality. This was never better dramatised than in his mournful ghost story, Ugetsu (1953). Meanwhile, Yasujiro Ozu continually returns to an ambivalent modern Tokyo, where old ways and older family members fade away in the face of a younger, consumerist, tide. Typically, this dynamic lies at the heart of his most beloved film, Tokyo Story (1953), and his final effort, a gloriously colourful yet melancholic return to the narrative of Late Spring, in An Autumn Afternoon (1962). Kinuyo Tanaka, herself a major star in films by the likes of Mizoguchi, Ozu, and Kurosawa, also made a significant impact as a director in an overbearingly patriarchal time and place. Her most acclaimed film, Forever a Woman (1955), stages the last years of the poet Fumiko Nakajo as a fight for dignity and passion in the face of oblivion. As we move towards and into the early 60s, we see Japanese cinema modernising in turn. Keisuke Kinoshita’s The Ballad of Narayama (1958) appears at first to be an anachronistic throwback: a widescreen, technicolour, and kabuki styled folk tale. A pastiche of form which opens a critical space for the savage traditions it depicts, as well as traditional modes of representation. We find a kind of malaise in the films of Mikio Naruse, with life stuck between a stifling past and an uncertain future. The bar hostess of When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960) is compelled to free herself from the yoke of oppressive tradition, even if it leads to her downfall. But the starkest critique of bureaucratic systems old and contemporary, within this season, is undoubtedly Masaaki Kobayashi’s stunning Harakiri (1962). An impeccably shot and scripted jidaigeki, featuring a signature performance from the great Tatsuya Nakadai, which feels as potently relevant to the injustices of today as it must have 62, or even 396, years ago.

Our final title, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) brings us to a transitional point in Japanese cinema. By this time, Mizoguchi and Ozu had died, Kurosawa and Kobayashi would soon be released from their studio contracts with Toho and Shochiku no longer willing to provide large budgets in the face of competition from TV, and a new generation of filmmakers such as Shohei Imamura, Nagisa Oshima, and Masahiro Shinoda were making the first of their provocative and political features. And while Kurosawa would never be associated with what would crystallise as the Japanese New Wave, High and Low is thrilling modernist neo-noir, that marked him as a director who would continue to evolve and delight, many decades after the early films which made his name.

The season features several expert introductions and a weekly post-film discussion group. This is the perfect space to unpack these contexts and more, to marvel in the highly individual styles of some of the key directors in global cinema, and to simply enjoy the experience of sharing these films with each other on the big screen. We will also be hosting a special sake tasting evening and screening to pay tribute to one of cinema’s great drinkers: Yasujiro Ozu.